The 30 foot Chinese Junk, Hai Jung (Sea Bear)

I think I first saw Hai Jung about 1972 in Glorietta Bay. If it was the same vessel, it was owned by a bunch of young hippie types, and the trim was dark green. The junk was at anchor and the deckhouse and spars were covered with laundry and the assorted debris that hippies collect. The vessel was a mess, but nonetheless, it had attractive lines.

I think I first saw Hai Jung about 1972 in Glorietta Bay. If it was the same vessel, it was owned by a bunch of young hippie types, and the trim was dark green. The junk was at anchor and the deckhouse and spars were covered with laundry and the assorted debris that hippies collect. The vessel was a mess, but nonetheless, it had attractive lines.

The next time I saw the vessel, and this time it was the Hai Jung, she was at the Navy Sailing Marina down Strand Way in Coronado. She was in a slip, and an older guy was working away on the dock alongside doing something with wood. I didn’t know at the time that the man was retired Marine LCOL Ed Collins.

Collins was a short man, and in Vietnam he had been given the job of riding up and down the Mekong river posing as a native while spying on the Viet Cong. He explained that this was relatively easy because the Vietnamese dialects changed so quickly on the river that you could not be detected by your speech patterns. He did not speak in any event. That was left to the skipper of the vessel. Being small, with a slight frame, brown eyes, heavily tanned skin and Vietnam native clothes he blended right into the culture. He also developed a love for the native craft, and it was this attraction that made him buy Hai Jung from the hippies.

What I did not know was that Collins had leukemia and knew he had a very short life expectancy. Perhaps as a metaphor to life he was devoting his energies to rebuilding the boat, and after repainting her in a more traditional black with red trim, he decided to begin with the interior.

Unfortunately he should have begun by restoring the watertight integrity of the hull. The Hai Jung leaked badly, and on several occasions, when the pump failed, or for other reasons, she sank at the dock. Fortunately the water was not deep and at low tide, using heavy duty pumps Collins and the marina people could get enough water out of her to have her back up and floating again.

I was deeply involved in watercolor painting at the time, and used to hang around the docks sketching, I became friends with Collins and began to follow the junks restoration progress. He did a beautiful job on the interior and made the vessel very habitable. Sadly, Collins died about a year later and the junk became a liability for his widow, Vera. I stepped in and bought the vessel for $4000.00 as it was.

Before the deal was completed I hired a marine surveyor who knew wooden hulls and junks, and had him give the boat a thorough inspection. This was a wise investment.

The first thing he did was to raise the floorboards and begin tapping the frames. He did know junks, and he knew that they were put together with iron nails. Iron nails rust, and at that time the was twenty years old. Many of the nails holding the hull together had deteriorated. Without the fasteners the frames and hull planks moved independently of one another. The planks then spit out the caulking that kept the hull watertight. THAT is why she sank so often.

After discovering the iron nail problem, I mentioned that I would replace all the nails with brass screws. The surveyor immediately said, “No! You have to replace iron nails with iron nails or galvanic action will occur and the boat will be in even worse shape”. He explained that I should mark the existing nails with chalk and then refasten the hull planks with nails positioned in between. I went on a search for iron nails and had to have them shipped in from a marine supply house in Washington State. Once this was accomplished we used a magnetic stud finder to locate and mark the old residual nails.

After discovering the iron nail problem, I mentioned that I would replace all the nails with brass screws. The surveyor immediately said, “No! You have to replace iron nails with iron nails or galvanic action will occur and the boat will be in even worse shape”. He explained that I should mark the existing nails with chalk and then refasten the hull planks with nails positioned in between. I went on a search for iron nails and had to have them shipped in from a marine supply house in Washington State. Once this was accomplished we used a magnetic stud finder to locate and mark the old residual nails.

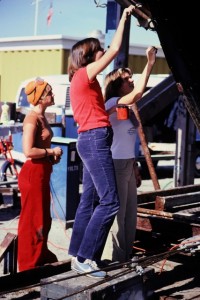

There was a small marine railway at the Navy sailing Marina and I managed to schedule four days to do whatever work I could accomplish in that period. My helpers were my daughters Lauren, Leslie, a friend of ours, Paige Giberson, my son, Chris, and various other folks who came and went. While Chris and I located and marked the old nails, then drilled and pounded home the new ones, the rest of the crew extracted the old seam caulking with special metal hooks. Then, armed with caulking irons and several skeins of caulking cotton, we pounded fresh cotton into the hull seams. In a way caulking is an art form. You must know how to twist the cotton and how hard to pound it into the hull seams. Luckily I grew up with wooden hulls back on Long Island Sound and as a kid I learned how to caulk a wooden hull. There were a lot of wooden hulls back then. The installed cotton was then covered with black seam compound.

I was due to launch at 0800 on the final day, and finished laying on fresh bottom paint about one half hour before that time (the type of bottom paint I used was designed to go into the water wet.

I was not a member of the Navy Marina and the waiting list was very long (maybe a year or two), so I powered the junk (it came with a 10 HP Mercury engine) to Glorietta Bay and put down a mooring using a 30 pound Danforth anchor, 30 feet of heavy chain and 5/8 inch diameter white nylon laid line.

It is appropriate to mention that all of the rapid yard work did not completely stop the leakage. Seepage still occurred, but it was seepage that was controllable. To this end I also purchased a heavy duty battery, an efficient small bilge pump and a water‑actuated on‑off switch.

Now we turned to the rigging. The temptation to sail the boat was pretty strong, so we took it out on the Bay several times and learned some of the basic techniques about junk sailing. Junks are tubby and heavy and in unskilled hands, very hard to sail efficiently. There is considerable side slippage which is somewhat controlled by a long dagger board forward and the large pierced rudder aft.

The main sail had sheets running to each of the battens, and lazy jacks attached to the lower boom so that you could reef the sail in a few minutes by lowering it into the lazy jack cradle. The boat did not come about very easily, especially when tight to the wind and in light airs. The reason for this is that coming about required momentum to carry her through, and the blunt bow, wide beam and drag of the dagger board all combined to keep her slow. We quickly learned to fall off on a beam reach to pick up speed and then throw the tiller hard over to swing the bow through the wind and keep her out of irons.

I especially remember one occasion when my pal, Dallas, and I were sailing her, and she was headed for the solid concrete tenth street pier. Dallas was at the helm and yelled, “Ready about”, threw the tiller over, and she barely got up into the wind when she fell off back on the original tack. He tried again with the same results. By now we were closing in on the pier with frightening speed. He finally yelled “Wear ship” and laid the tiller off to turn downwind. That was our first jibe, but not our last use of the “wear ship” command.

On one trip I towed our small ten foot inflatable along and then used the small boat as a platform for junk photography. Kodak owes us a debt for all of the rolls of film expended by people on the harbor cruise and by guests on my boat. In any event, on this occasion I took pictures of the boat under sail from a variety of angles. It was only when the photos were developed that I noticed that the fore and aft sails were on upside down. They had been this way since Collins owned her and maybe before. Another lesson about junk rigging.

On one trip I towed our small ten foot inflatable along and then used the small boat as a platform for junk photography. Kodak owes us a debt for all of the rolls of film expended by people on the harbor cruise and by guests on my boat. In any event, on this occasion I took pictures of the boat under sail from a variety of angles. It was only when the photos were developed that I noticed that the fore and aft sails were on upside down. They had been this way since Collins owned her and maybe before. Another lesson about junk rigging.

By now junk sailing had become quite a lot of fun, so we made the decision to make new sails using a colored nylon material called “tanbark”. I was not particularly intimidated by the need to make our own sails. Junk sails in Asia are anything but precision sewn. In China, and elsewhere in Asia, whole families will sit side by side stitching patches of cloth together, and there is no worry about tapered seams or proper belly. I used the old sail gores as a pattern and my Singer sewing machine for the stitching. Lauren solved the problem of sewing large pieces of cloth together by suggesting that each side be rolled. The two rolls could then be pushed past the needle, seam to seam, without wadding up.

In addition, some of the bamboo battens needed to be replaced. We solved that problem by cutting fresh bamboo that had sent underground rizomes under the fence at the Balboa Park nursery and then grown tall. The park people welcomed us since clearing this unwanted stuff was one of the chores they had to perform. We discovered that green bamboo left in the sun to dry will split. Our new trees were put away in the shade where they aged gracefully.

The bamboo battens are actually stitched to the sail, and this was tedious work. I bought a sailor’s sewing palm and some large sail needles and accomplished the work over a week’s period of time. Some of the rigging had to be replaced, but we discovered that the mast was set in a tabernacle and could be lowered by removing the bottom of two pins. This allowed us to inspect and repair all of the topmast lines and splices. The dead eyes that secured the shroud lines required cleaning and new 3/8 inch nylon tightening lines to be safe. All this took time and a lot of sanding and line splicing, but the vessel was coming to shape and looking good.

The boat was constantly at anchor off the Coronado Golf Course, and during the day there is a fairly steady northwesterly breeze. This meant that the boat streamed off on an south easterly direction with its port side almost always exposed to the sun. I did not realized the consequences of this until one sailing trip when we had run down the bay to Shelter Island on a port tack, and then came about to cross the Bay on the other tack. One of Lauren’s friends, who had been below, came up and asked me if it was alright to have water pouring through the cracks in the side. I flew below and, sure enough, I could see dark green spaces between the planks where the water WAS pouring in. The constant exposure of the black hull to the sun had caused the upper hull planks to shrink-hence the leak. We dropped the sail, got the hull on an even keel and motored back to the mooring. More caulking cotton and more seam compound solved the problem, but we were vigilant ever after that.

Even without that, sailing the junk was an interesting experience. Often the currents in the bay were stronger than the push of the sail, and I expect we hit almost every buoy in the Bay and least once when we were unable to spin the boat around fast enough. I also discovered that on a beam reach I could adjust the three sails so that the boat would hold its track without using the rudder. This was handy when sailing down the long part of the Bay opposite downtown.

At some point Leslie asked me if she could live on the vessel with her friend, Sep. I agreed to this and she lived on the boat for several months. As I said, the interior was well laid out and the beamy hull allowed for plenty of room. There w as also a functioning “head” aboard and a small decent galley. I expect the constant need to row back and forth to the beach and the lack of entertainment made the girls quit the junk for solid land and more traditional quarters, but it had to be an interesting experience.

About this time Darlene and I were splitting up and since I was back into watercolor painting I began going out with Kay. The junk was STABLE and we quickly found that the big flat roof made a perfect platform for us to set up our easels and paint the ships and vessels that lined the bay. It was a perfect arrangement because we had a completely new perspective on our subject matter and no kids dribbling ice cream down our legs trying to look at our work. The downside was that Kay’s big floppy hat kept flying off and into the water. The boat-hook helped here, but the hat definitely became one that an old salt would be proud of.

The hull always needed some work and I found the yard at Kettenburg Marine perfect for us. They had a large marine railway for hauling and good solid supports to keep the boat on an even keel while we worked on her. There was also a store where we could purchase marine supplies and nearby places where we could eat. I hauled the boat out there at least twice.

The last haul-out began with an interesting twist. Lauren was my crew and we used the small 10 horse Mercury engine to motor from the anchorage by the Coronado golf course to the bay at Shelter Island where Kettenburg was located. The heavy boat was a bit of a load for the small engine which required almost full throttle. This chewed through our gasoline supply much more quickly than I had anticipated, so just as we turned into the Shelter Island Bay the engine quit. I had thought of this possibility, so I had an anchor ready on the foredeck. I had Lauren toss it over the side. What to do?

I remembered that there as a set of long sweeps (oars) down below. We had never used them and they were stowed somewhere, so I looked around, found them and brought them on deck. On either side of the cockpit there were thole pins (the forerunner to oar-locks). The sweeps were each ten feet long, so we could row with them while standing up. Lauren had one side and I the other. We hauled the anchor and then proceeded to row the boat up the channel to the yacht yard. The folks on shore saw us, of course, and pretty soon the chant of Yo Heave Ho was floating across the water to give us encouragement. I’m glad I don’t embarrass easily.

After several years and hours of fun it became time to sell Hai Jung. It didn’t take long. The boat was in good shape and able to sail and a great curiosity. Not only that, it was made of teak, so the intrinsic value of the wood was good insurance to the buyer.

A couple from Oceanside bought her, but part of the deal was that I would go with them when the moved the boat from Glorietta Bay to marina in Mission Bay. An old pal of mine had died and been cremated and had told his widow that he wanted his ashes poured out at sea. She happened to be in town with the ashes on the day of the big move so I invited her along. Understandably I didn’t want to tell the new owners that they would be sailing funerary on their first cruise, so half way up Point Loma, when we were bobbing along in a good breeze I signaled below that ash-dropping time had come. It is still a fond memory to think about that long slender female arm reach out of the deck house window unobserved and pour Rodney’s remains into the Pacific. My old pal would have been proud. Fair winds and following seas!