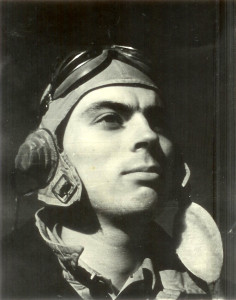

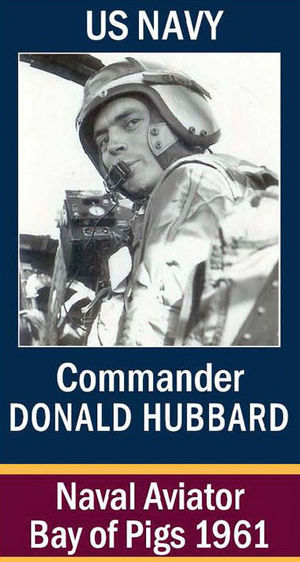

Don Hubbard was born in the Bronx in 1926. As high school graduation loomed, there was no question that he would do what every other young man in his class was doing. He would enlist as soon as he could. Following the advice of his Navy pilot brother in law who was eight years older, Hubbard enlisted in the naval aviation candidate program (V-5) on Nov. 9, 1943 at 17 years old. He became a Naval Aviator after World War II concluded, in April 1947.

Don Hubbard was born in the Bronx in 1926. As high school graduation loomed, there was no question that he would do what every other young man in his class was doing. He would enlist as soon as he could. Following the advice of his Navy pilot brother in law who was eight years older, Hubbard enlisted in the naval aviation candidate program (V-5) on Nov. 9, 1943 at 17 years old. He became a Naval Aviator after World War II concluded, in April 1947.

At the time, the armed services were paring down. Hubbard had been so impressed with the Navy way of life, he decided he wanted to stay longer than four years and make it a career. He enjoyed flying and he was being paid to fly. What could be better than that?

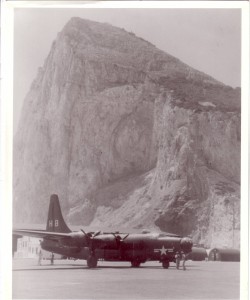

Hubbard was sent off to his First squadron, Heavy Patrol Squadron 26 (VP-26). His Squadron Mission was Top Secret “Ferret Flights” searching for communist radars. He was based out of Morocco, but operated in the Baltic and Adriatic Seas along the periphery of the communist countries. Between 1947 and 1950 Hubbard flew on 21 of these highly classified missions. In May 1950 one of the squadron planes was shot down by the Soviet Union, off Latvia, killing all 10 crewmen. It was the first casualty of the Cold War. The squadron was returned to the United States, but the mission was considered so vital to American interests that it was given new faster aircraft and reclassified as VQ-1, the Navy’s first electronic eavesdropping squadron.

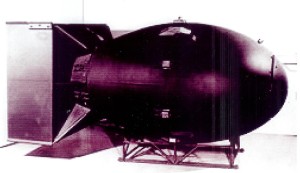

Hubbard’s Second Squadron was the Composite Squadron 6 (VC-6). This squadron had only one mission: dropping nuclear weapons (Fat Man – 21 kilotons) if the enemy used them in Korea. Our “Fat Man” was a 10,300 lb. nuclear bomb, identical to the one that was used to bomb Nagasaki. Don was one of perhaps 300 naval aviators trained for this dangerous mission, Captain Roy Mantz who also lives in Coronado was another one, and flew in the squadron for three years as a plane commander. The squadron flew the specially built AJ-2 “Savage” carrier-based aircraft that could climb to 45,000 feet for this mission and required special oxygen masks that forced air into the lungs at that thinned low atmospheric pressure altitude to provide enough oxygen.

Next up for Hubbard was the Third Squadron: VP-63. This was a hi-altitude photo squadron based out of Jacksonville. Among other classified photo missions the squadron mapped the beaches in Cuba in preparation for the later Bay of Pigs invasion and then took the pictures of the invasion itself on April 17, 1961. Hubbard personally flew these nine canisters of aerial photos and the initial photo analysis report to Washington, DC for President Kennedy’s briefing the next morning.

In June 1961 Hubbard received “immediate” orders to Commander Naval Base, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to be the admirals’ air officer to take control and direct all of the surveillance missions being flown around the eastern end of Cuba before and after the “Missile Crisis.” Hubbard’s wife and two children (and all other 2,500 dependents) were evacuated by Navy warships on six hours’ notice when President Kennedy declared the Cuban Missile Quarantine. Hubbard’s family and 350 other dependents were placed aboard a seaplane tender with a crew of 200. They spent four days on these four warships while they made the transit to Norfolk, VA. His daughter, Coronado resident Leslie Crawford, and son Chris Hubbard were passengers during this evacuation. It was later learned that Chairman Khrushchev had a nuclear tipped cruise missile stationed 15 miles NE of the base to be used to destroy Guantanamo if the Americans actually landed elsewhere on Cuban soil.

In 1966, as a commander in his final overseas duty, Hubbard volunteered to serve in Vietnam for a year. He worked both at General Westmoreland’s Military Assistance Command in Saigon, and flew twin-engine transports carrying cargo and passengers throughout the country, often landing on short, hastily built jungle runways to deliver supplies. He received an Air Medal for these flights.

Hubbard then retired from the Navy on June 30, 1967. He had spent 24 years flying in the Navy.

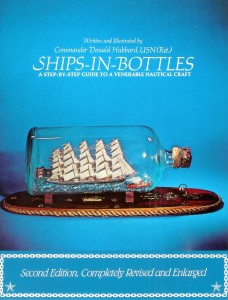

After retirement he wrote four full length published books: “Ships-in-Bottles: A Step-by-Step Guide to a venerable Nautical Craft” (McGraw-Hill) (David & Charles, Ltd in England) and (Vorlag Delius Klasing in Germany) 65,000 copies total; “The Complete Book of Inflatable Boats” (Western Marine Publishing) 3,500 copies; “Neptune’s Table: Cooking The Seafood Exotics” (Sea Eagle Publications) 3,000 copies; and “GITMO: The Missile Crisis” (Electronic book on Amazon Kindle).

He is currently a volunteer serving as a World War II briefer on board the USS Midway Museum.